The Lions Gate Bridge, opened in 1938, officially known as the First Narrows Bridge,[1] is a suspension bridge that crosses the first narrows of Burrard Inlet and connects the City of Vancouver, British Columbia, to the North Shore municipalities of the District of North Vancouver, the City of North Vancouver, and West Vancouver. The term “Lions Gate” refers to The Lions, a pair of mountain peaks north of Vancouver. Northbound traffic on the bridge heads in their general direction. A pair of cast concrete lions, designed by sculptor Charles Marega, were placed on either side of the south approach to the bridge in January, 1939. [2]

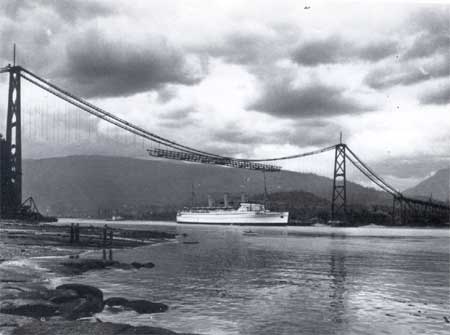

The total length of the bridge including the north viaduct is 1,823 metres (5,890 feet). The length including approach spans is 1,517.3 m (4,978 ft), the main span alone is 473 m (1,550 ft), the tower height is 111 m (364 ft), and it has a ship’s clearance of 61 m (200 ft). Prospect Point in Stanley Park offered a good high south end to the bridge, but the low flat delta land to the north required construction of the extensive North Viaduct.

The bridge has three reversible lanes, the use of which is indicated by signals. The centre lane changes direction to accommodate for traffic patterns. The traffic volume on the bridge is 60,000 – 70,000 vehicles per day. Trucks exceeding 13 tonnes (14.3 tons) are prohibited, as are vehicles using studded tires. The bridge forms part of Highways 99 and 1A.

On March 24, 2005, the Lions Gate Bridge was designated a National Historic Site of Canada.[3]

Lions Gate Bridge under construction

Starting about 1890, bridge builders saw that a bridge across the first narrows was becoming a possibility. There were a number who argued against its construction, as many felt it would ruin Stanley Park or cause problems for the busy seaport or that it would take toll revenue away from the Second Narrows Bridge. However, many others saw it as necessary in order to open up development on the North Shore and it was felt that these problems could be overcome. The decision was put to the electorate of Vancouver in 1927, but the first plebiscite was defeated and the idea was put to rest for a short while.

Alfred James Towle Taylor, who had been part of this proposal and still owned the provincial franchise to build the bridge, did not have the finances to purchase the necessary large sections of property in North Vancouver and West Vancouver. However, he was able to convince the Guinness family (of the Irish stout fame) to invest in the land on the north shore of Burrard Inlet. They purchased 4,700 acres (16 km²) of West Vancouver mountainside through a syndicate called British Pacific Properties Ltd.

On December 13, 1933, a second plebiscite was held and this time, it was passed by a 2 to 1 margin. After considerable further negotiations with the federal government, approval was finally granted, with the requirement that Vancouver materials and workmen be used as much as possible to provide employment during the Great Depression. The 1933 bylaw authorizing construction included a provision mandating that “no Asiatic person shall be employed in or upon any part of the undertaking or other works.”[4]

The bridge was designed by the Montreal firm Monsarrat and Pratley, which was later responsible for the Angus L. Macdonald Bridge in Halifax, Nova Scotia using a similar design. Other companies involved in the construction of the bridge include: Swan Wooster Engineering, Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Rowan Williams Davies & Irwin Inc., Canron Western Constructors, Dominion Bridge Company, American Bridge Company.[5]

Lions Gate Bridge as seen from the air

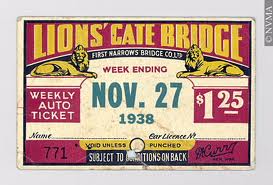

Construction began on March 31, 1937. After one and a half years and a cost of $5,873,837.17 (CAD), it opened to traffic on November 14, 1938. On May 29, 1939, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth presided over the official opening during a royal visit to Canada. A toll of 25 cents was charged for each car. You could get a weekly pass for $1.25… Chip not included!

On January 20, 1955, the Guinness family sold the bridge to the province for $5,959,060, and in 1963, the tolls were dropped. The newly constructed bridge differed from the current configuration of the bridge as it originally had only two lanes. Yet, as had been foreseen, West Vancouver’s population boomed as a result of the new connection. Thus, to accommodate the increased population, the lanes were divided into three with the middle lane acting as a passing lane. Another difference with the original configuration was that in an effort to recover the expenditure it cost to build the bridge, the Guinness family had toll booths installed. The toll booths remained on the bridge until 1963, at which time the bridge was purchased by the provincial government for the same price that it took to build it. Changes were made shortly after the takeover, as the tolls were removed and the overhead lane controls were added. The Guinnesses’ last involvement with the bridge happened in 1986, when they added lights to the bridge as an Expo ’86 gift.

The bridge was originally constructed as a two-lane bridge, but when traffic increased, the road was repainted to create a third lane, which was originally a passing lane. Eventually overhead lane control signals were installed, enabling traffic in the centre lane to be directed in either direction.

In 1975, the deteriorating north viaduct was replaced with a lighter, wider, and stronger steel deck with wider lanes. This was carried out in sections using a series of short closures of the bridge; each time, one old section was lowered from the bridge and its replacement was put into place.

In 1986 A Bright Idea Became the Gift of Lights from the Guinness Family

In 1986 the Guinness family, as a gift to Vancouver, purchased decorative lights that make it a distinctive nighttime landmark. In July 2009, the bridge’s lighting system was updated with new LED lights to replace this existing system of 100-watt mercury vapour bulbs. The switch to LEDs is expected to reduce power consumption on the bridge by 90 per cent and save the Province about $30,000 a year in energy and maintenance costs. The approximate cost to of this project was $150,000, paid for by the ministry and B.C. Hydro. “The average replacement time of one of the traditional light bulbs was about 72 hours,” said the ministry’s Jeff Knight. With the new LED bulbs, which are designed to last 12 years, it could be a decade before any work crew is called out to do a replacement.

By the 1990s, it was time for the bridge to be either significantly upgraded or replaced. A number of different proposals were considered, including building a new bridge beside the existing bridge, building a tunnel from Downtown Vancouver to the north shore, or double decking the existing bridge. However, none of the proposals could overcome the City of Vancouver’s objections to any increase in traffic into the downtown core and the province’s unwillingness to spend much money on the project. In the end, it was decided to upgrade the existing bridge without adding any new lanes.

Traffic was finding the 2.84 m (9 ft 4 in) wide lanes narrow, and the sidewalks were inadequate for pedestrians and cyclists. As a result, the main bridge deck was replaced in 2000 and 2001 – the first time a suspension bridge’s deck had been replaced. As with the earlier work, this was facilitated by a series of separate nighttime and weekend closures to replace one section at a time. The old section would be lowered to a barge, and the new one raised into place and connected. The change allowed the two pedestrian walkways to be moved to the outside of the structure and the road lanes were accordingly widened from 3 to 3.6 m (from 10 to 12 ft) each; the new sidewalks are also wider, 2.7 m (9 ft) each instead of 1.2 m (4 ft). Also, the main structural elements were moved to below the bridge deck, thus giving a much more open appearance. The entire suspended structure was thus replaced with little or no interruption in daytime traffic

For More Info: http://www.mccord-museum.qc.ca/en/keys/webtours/GE_P4_3_EN.html

The Lions Gate Bridge is always a favourite in TV shows and with Tourists. It’s a World Famous Vancouver Attraction featured with Stanley Park in more than 20 million pictures!

Leave a Reply